Last month, I was privileged to return to the University of Chicago, my alma mater and the institution where I spent most of my career, to deliver a talk as part of the MacLean Center’s lecture series on gender equity and ethics in medical education. In the course of preparing my talk, I was struck by how resistant the profession of medicine has been to making real change for gender equity. The lack of progress over decades is unlike what we see in so many other aspects of the practice of medicine. Our profession is one which has incorporated stunning changes in science and technology, taking astonishing scientific breakthroughs and technological innovations and figuring out how to bring these achievements to the bedside for the enduring benefit of our patients. Given the flexibility and adaptability that the profession of medicine has shown in this regard, it strikes me as ironic and deeply disappointing that our profession has been so resistant to equally important societal, demographic, and cultural forces that would help us to take better care of the people who are the lifeblood of the profession. We could do so much better.

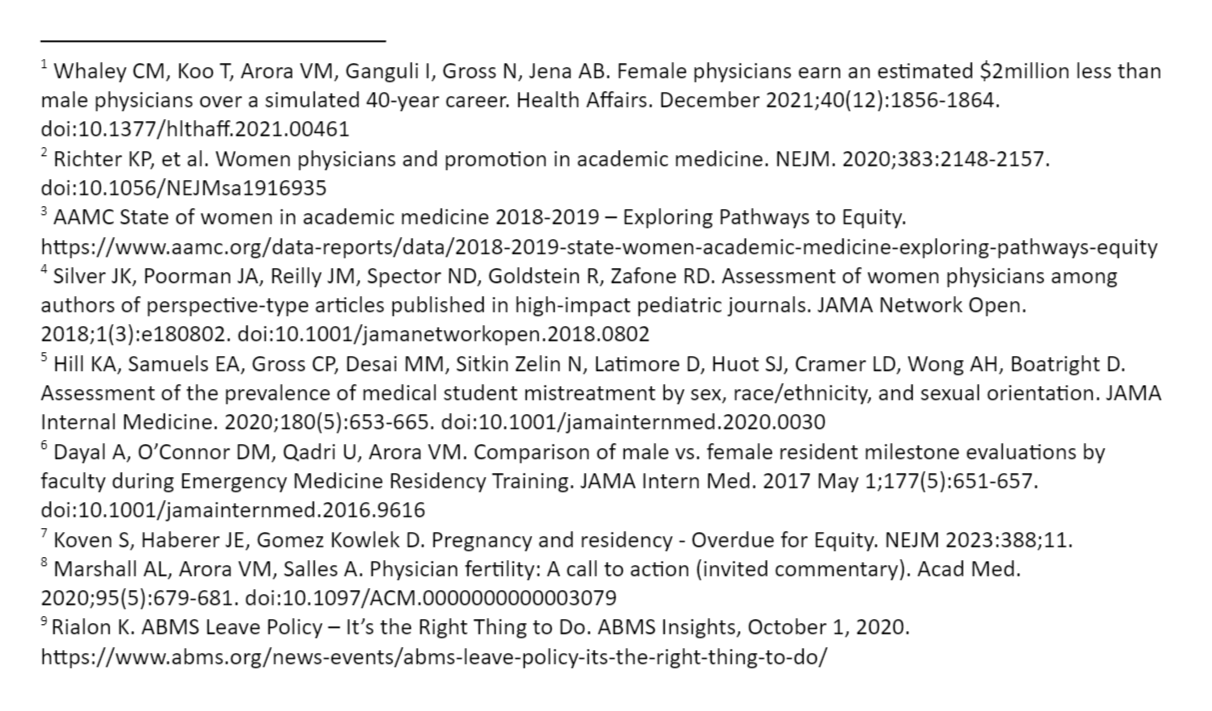

The literature and data related to the advancement of women in medicine paint a very bleak picture. There are documented gender disparities in professional opportunities, including differences that women experience in pay and opportunities for promotion compared to men. Women are underrepresented in senior faculty roles and leadership across academic medicine. They are less likely to have their original research or perspective articles published in high-impact journals. Medical students and residents who are women are more likely to encounter mistreatment in the clinical learning environment and to experience bias in the grading and assessment of their performance.

One of the most concerning ways in which the profession of medicine has shown itself inhospitable and resistant to evolution is through the deleterious impact that medical education and medical practice have on women who seek to have children. The length of medical education is such that the average age at which most female physicians first give birth is 32, while the average age for non-physicians to give birth is 27. Further, the lived experience of medical training and practice, including sleep deprivation, poor diet, and lack of exercise, has a negative impact on both fertility and the health of pregnant women.

For those women who do give birth during training, it is remarkable that not until July 2021 did the American Board of Medical Specialties implement a policy allowing residents to take one six week leave away from training for parental, caregiver, and medical leave without requiring an extension in training. For female physicians in particular, allowing greater flexibility in training was a necessary and crucial step toward gender equity, but it is by no means sufficient to address the ongoing work-family tensions that have for far too long required painful sacrifices for physician parents and their children.

Just this month, we published a story on our website featuring a grant awarded last year by the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation to two medical students, Hannah Caldwell and Dru Brenner, at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. The Parent Resources in Medical Education (PRIME) Initiative is exploring systemic solutions to make the profession of medicine one which is more welcoming and supportive of parents and their children. I urge you to read about the concrete steps that they are taking and the programs that they are implementing, which we hope will ensure that the next generation of physicians and their children are not forced to make the same painful sacrifices that prior generations experienced. We applaud their efforts, and we root for their success. We are grateful once again to our learners, who are helping to work toward a more hopeful and inclusive future for our profession.

NOTE: In speaking of gender, I do want to make it clear that the data and literature I am referencing take a binary view which in no way reflects the complexity of gender or the complexity of issues related to gender.