In response to my November 2022 interview with Dr. Mary Owen, in which she shared details about the Center of American Indian and Minority Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School, Duluth Campus, I received a thoughtful note from Robert Cain, DO, FACOI, FAODME, and Natasha Bray, DO, MSEd, FACOI, FACP. As the President and CEO of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic Medicine (AACOM) and Dean of the Oklahoma State University College of Osteopathic Medicine (OSU-COM) at the Cherokee Nation, respectively, Drs. Cain and Bray have much knowledge of and experience with the significant work that osteopathic schools, including OSU-COM, are doing to advance Indigenous health. During our recent conversation, they shared their thoughts and inspiring experiences with me.

Dr. Holly Humphrey (HH): We are all aware of that the US is facing a significant projected shortage of physicians—particularly primary care physicians. Dr. Cain, I know you had a chance to work on that issue with the Macy Foundation more than a decade ago with my predecessor Dr. Thibault. What is AACOM doing to address this issue on its own and in collaboration with other key organizations?

Dr. Robert Cain (RC): The projected shortage of primary care physicians threatens our ability to deliver needed healthcare services across the country, particularly in rural and underserved areas. AACOM is a close community strengthened by a shared philosophy and focused on whole person care. Because of that shared philosophy, AACOM and the osteopathic community have been committed to delivering what we today know as primary care for the past 125 years.

The mindsets, methods, strategies, and structures of the osteopathic curriculum inherently create a primary care lens to which all osteopathic medical students are educated. Entry into primary care is a natural outgrowth of osteopathic medicine’s approach to medical education, one element of which is training people in the communities where they will practice. Last year, 55% of graduating DO medical students went into primary care. We’ve opened a number of new schools, many of which are located in rural and medically underserved areas. According to our available data, 60% of US colleges of osteopathic medicine are located in a federally designated health professional shortage area, 64% require clinical rotations in rural and underserved communities, and nearly 90% include rural and underserved communities in their mission or publicly facing documents. So they are well-poised to not only help address that primary care shortage, but to do it in areas of the country where there is the greatest need.

HH: Having enough physicians is clearly important, but having a physician workforce that more closely resembles the patient population that they will serve is also crucially important for the health of the public. What can be done to increase the percentage of students who are from American Indian and Alaska Native backgrounds?

Dr. Natasha Bray (NB): We have a lot of opportunities to grow the Native American physician workforce. The first opportunity is in pathway programs, which reach out to rural and tribal communities and expose students early in their developmental and educational careers to the notion of, “I can be a doctor.” We do this at multiple levels, whether it’s our Teddy Bear clinics where we go into elementary schools or at the high school level with programs like Operation Orange, which exposes students to an array of fields in the health professions.

We also have programs for our Native American students who are in small community colleges across the state where we support them in developing themselves to get into medical school, which includes a mentoring component.

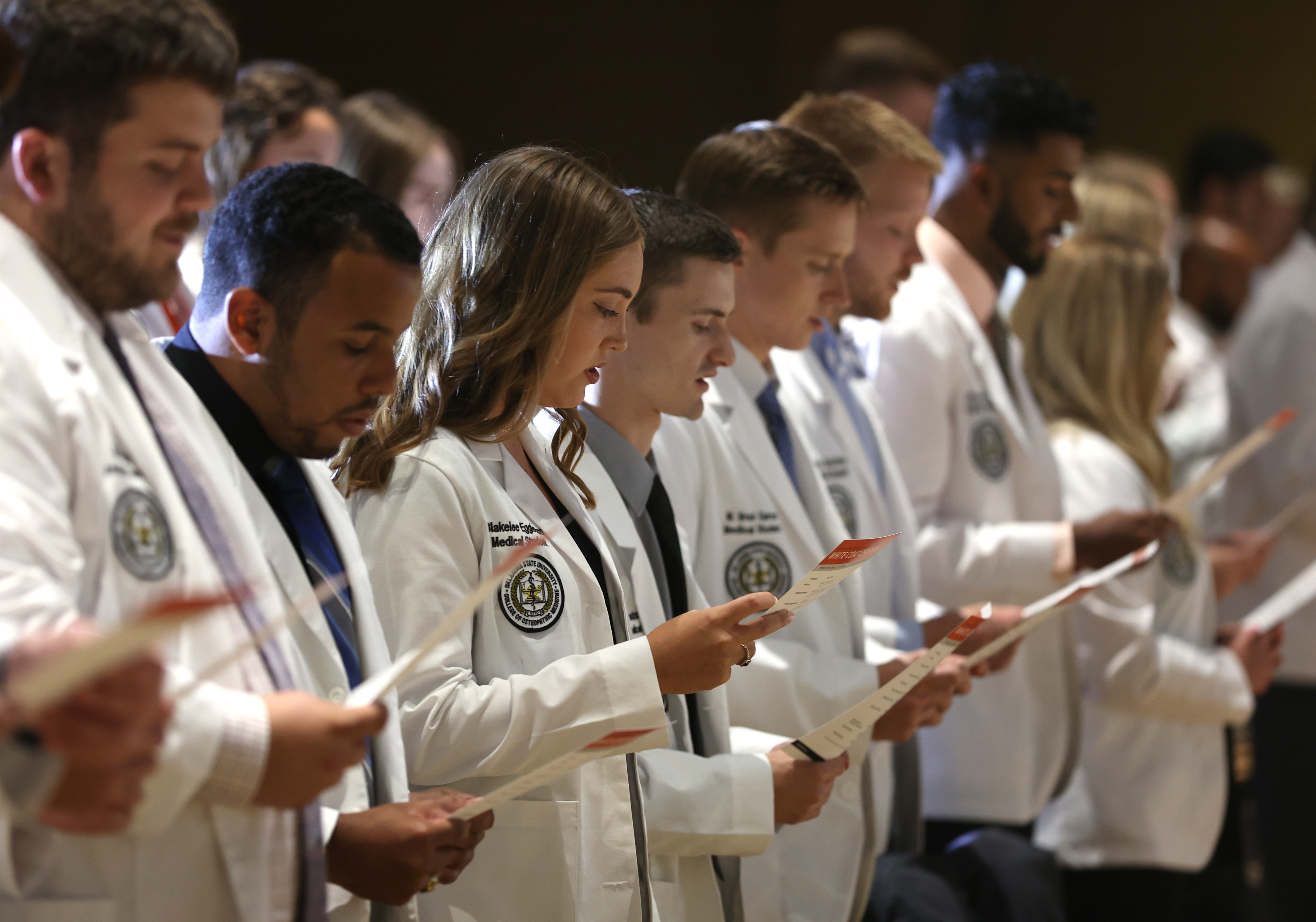

Once they get to us in medical school, we think we offer a unique environment at OSU. We’re the only tribally affiliated medical school that’s in a rural community on the Cherokee Nation reservation. We sit next door to WW Hastings Hospital, which is the Cherokee Nation’s primary hospital and across the parking lot from their ambulatory clinic that serves as a multi-specialty medical home for Cherokee citizens. Our school is culturally based, from the seven pillars that are on the front of the school representing the seven clans of the Cherokee Nation to the traditional healing plants that are outside of the school. We have extensive Cherokee art within the school that goes throughout, creating an educational environment where our students, whether they’re Cherokee or from one of the other tribes from Oklahoma or across the nation, or our students from rural communities, are empowered to bring their whole selves into our learning environment.

As they move through the curriculum, we have programs that support students in staying in contact with their tribe and with their community, so they develop and understand their role in a different way. We have a tribal medical training track which places them in clinical rotations in tribal-based clinics. We developed tribal residency programs with the Cherokee, Chickasaw, and Choctaw Nations. We aim to create an environment that nurtures students, creates opportunity, and ensures they have the residency training they need to go back and serve their tribal communities.

HH: Let’s talk for a moment about your school’s history, Dr. Bray. In 2020, OSU-COM partnered with the Cherokee Nation to establish the nation’s only tribally affiliated medical school. How did this partnership come about and what do you hope will be accomplished by this collaboration?

NB: It came to be through a lot of trust developed in conversations and listening—listening with intent—and then employing creativity in using the medical educational system to train physicians in a way that meets the community’s needs.

The Cherokee Nation, a 14-county reservation, made a commitment in the early 2000s to invest in health for their citizens and open a primary care medical home in the region so that no citizen that lived within the 14-county reservation was more than 35 miles from a clinic. These are beautiful facilities, but what they discovered is they didn’t have physicians to staff them. The Cherokee Nation reached out to OSU and asked how could OSU, an institution that has been invested in training rural primary care physicians since 1972, translate that focus to the Cherokee Nation’s health care space? It started with student rotations; the students wanted to complete their clerkships with the Cherokee Nation. In 2007, OSU in partnership with the Cherokee Nation in Northeastern Health System, the community hospital in Tahlequah, opened a family medicine residency program.

In 2012, we began to have conversations around the possibility of opening a medical school campus in Tahlequah and considered how we would we do so in a way that is meaningful and would ensure the academic success of our students. We want to train people who are highly competent and skilled, and also very respectful of the Cherokee Nation’s culture, heritage, and contributions.

HH: There are likely many important lessons we can all learn from the experience that you and your colleagues are having and from this rich history on which your school is built. Are there a few lessons that stand out in your mind that may be helpful and applicable to health professions schools broadly?

NB: The first is to look at your community. When you identify a need in the community, go and ask and listen to what community members perceive the needs to be. As educators, we often try to solve problems, but we don’t listen to what the priorities and the problems are. By putting ourselves in a more passive position to hear what the community needs and how they would approach solving that problem is a first step to healing communities.

The second is to be willing to acknowledge and recognize that you’re going to make mistakes. Whenever we confront things that are different or unfamiliar, we interpret them through our own lens, as much as we try not to. Therefore, it is important to be present and listen and be willing to change course if needed.

The third lesson is that it is okay to bring your expertise and to think creatively to solve problems in a different way. For example, how do we talk about backgrounds of our patients? Do we describe them in patient-centered language so that we’re making sure that we’re being sensitive to communities that might not have the same cultural beliefs that we do? By bringing in students, faculty, and staff from different backgrounds to an environment where they feel safe to share their experiences, we can create a rich learning environment that prepares learners to care for many communities.

HH: Dr. Cain, let me go back to you. Do you have any other thoughts about the lessons that we can learn from what you and your colleagues are doing, and from what Dr. Bray and her colleagues are doing at a local level?

RC: This is an inspiring story because this school is located on tribal land, but we have numerous schools that have commitments to Native populations. For example, at Pacific Northwest University there is a program in co-mentoring and design. Programs like OSU’s and Pacific Northwest University’s will be the catalysts. It takes shared vision, commitment, partnership, and—most importantly—trust.

Osteopathic principles by nature promote interconnectedness of things, and that’s something that’s recognized and embraced broadly in Native culture. The work at OSU is a reminder that osteopathic medicine’s historical core values of holistic healing and whole person care create opportunities to focus on the social determinants of health and health equity.

HH: Yes, it is a powerful testimonial listening to what Dr. Bray and her colleagues are doing in Oklahoma, but also the bigger picture of osteopathic medical schools in general. There is a certain cultural humility that I heard Dr. Bray describing that is so powerful in trying to accomplish and live up to those principles that you articulated. Thank you.