In 2015 the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine delivered their seminal report on the current state of diagnostic errors, concluding that most people will experience at least one diagnostic error in their lifetime, sometimes with devastating consequences. The report also delivered eight major recommendations on how to potentially improve diagnosis, one of which was to improve the education of all health care providers.

Together with four medical schools and their partner health professional schools, the Society to Improve Diagnosis in Medicine (SIDM)—with support from the Macy Foundation—is taking the first steps towards developing a new curriculum to educate health professionals about how to improve diagnosis.

“Diagnostic errors are one of the biggest concerns patients have today,’’ says Dr. Mark Graber, principal investigator for the project and Chief Medical Officer at SIDM. “The fact that 1 in 20 primary care patients will experience a diagnostic error this year, and every year, is one that we can’t ignore any longer.”

When asked why diagnostic errors are so pervasive, Graber explained that diagnosis—and medicine in general—is increasingly complex. In addition, most students today are learning about diagnosis simply by observing their faculty leaders, with no courses currently dedicated solely to diagnosis. And finally, health professionals continue to both learn and work in silos, whereas experts believe increased teamwork can dramatically reduce diagnostic errors from occurring.

“We are convinced, and have strong evidence, that if health professionals work together in teams we will improve diagnosis and avoid diagnostic errors,’’ says Diana Rusz, MPH, a co-investigator for the project and Program Manager at SIDM. “Teamwork is effective in aviation, the space industry, business, and many other sectors. It only makes sense that we work in teams when caring for patients. Simply put, teamwork improves performance.’’

Building the New Curriculum

To design the new curriculum, SIDM spearheaded a robust literature review and curriculum assessment to identify where educational gaps existed. The team also convened a multidisciplinary Consensus Committee that included clinicians and educators from internal medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, nursing, pharmacy, laboratory sciences and radiology, as well as patients, to determine what competencies are needed for safe and effective diagnosis.

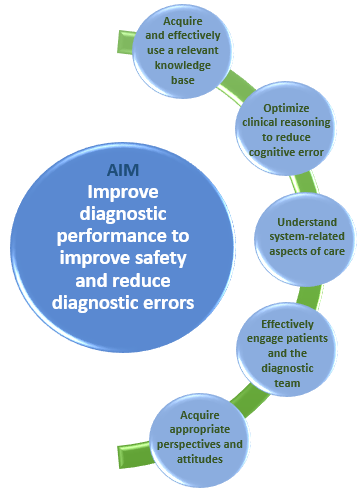

The committee first identified five key drivers through which education can ultimately improve diagnosis:

Based on the key drivers, the committee developed a set of 12 recommended competencies, organized into three overall domains: individual, system-related, and team-based competencies. Each competency includes a set of learning objectives and sample milestones to track learner progress. The competencies, by design, apply to training in every healthcare profession.

“These cross-cutting competencies lay the foundation for how we can begin to reduce diagnostic errors and are important building blocks for providers as they learn about the diagnostic process,” explains Dr. Graber.

Dr. Andrew Olson, co-leader of the project and an Assistant Professor of Medicine and Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School, said, “These competencies are fundamental to improving education because they delineate the outcomes we want to achieve with respect to diagnosis in our education programs, allowing us to measure learners’ progress.”

Supporting Diagnostic Safety Education

The recommended curriculum will help students better understand that errors do occur and how they transpire, and learn to communicate and work more effectively as a team. In addition, learners and their faculty will be better equipped to understand how humans make decisions and how the diagnostic process works. How the new curriculum will be implemented will be up to each school, but having this new set of competency expectations sets a new direction for healthcare education and training.

“The goal of this curriculum is to convey the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to optimize the quality and safety of the diagnostic process, in every healthcare profession,’’ says Dr. Graber. “We want to ensure that the next generation of providers is better able to steer clear of diagnostic errors.”

To Err is Human

The curriculum spells out the new competencies and content for educational programs and complements a growing set of resources SIDM has compiled or developed to support education about the diagnostic process. Many of these resources are part of SIDM’s Clinical Reasoning Toolkit, a resource library for educators interested in teaching clinical reasoning. In addition, SIDM has developed the Assessment of Reasoning Tool, an easy-to-use tool to enable teachers to give high-quality, actionable feedback to learners about clinical reasoning.

“What’s really exciting and unique about this project is that we are essentially also talking about culture change,’’ Rusz says. “No health care professional goes to work wanting to harm a patient. But when errors do happen, there is a lot of stigma around it and we’ve created an environment where errors aren’t talked about. It is important that we change attitudes and mindsets around reporting and discussing errors. Reflection, team communication, learning to accept uncertainty, and incorporating the patient’s feedback will help create a learning ecosystem so that the same error doesn’t occur repeatedly.”

There is No “I” in Team

SIDM’s curriculum focuses heavily on teaching health professionals together. Working together, teams of health professionals will use the training materials and real patient case studies to discuss what occurred and create a plan for how to avoid the mistake in the future.

Another major component of SIDM’s curriculum is teaching students to engage patients in the diagnostic process. Encouraging patients to ask questions and be more proactive in their care, Rusz says, will help cut down on errors. It will also empower patients and ensure their values and preferences are honored. Teaching students to do this from the start is important and avoids the need to re-train later.

Road-Testing the Curriculum

Later this year, four medical schools and their partner health professional schools will pilot SIDM’s curriculum. Pilot sites include the University of Minnesota, the University of North Carolina, the Dell Medical School (University of Texas at Austin), and the University of North Texas Health Science Center.

Because the curriculum is so customizable and adaptable, each school will implement it in different ways. The University of North Carolina, for example, will create a new course on diagnosis that will be attended by medical, nursing, and social work students, while the University of Minnesota will embed the curriculum for medical students and other health professional students while continuing to expand its longstanding curriculum for pediatric residents.

Heading up the University of Minnesota effort is Dr. Andrew Olson, co-Chair of SIDM’s Education Council and co-leader of the Macy Foundation project.

“Changing curriculum is hard, but it is important and must be done,’’ says Dr. Olson. “Diagnosis is the most important thing we do in health care, and we have to do a better job equipping our learners to practice high-quality, safe, and timely diagnosis. Every diagnosis is made in a team and thus we should teach it in teams.”

“Even if institutions start small with one profession and then expand to include more professions, that’s a win,” Rusz adds. “Hopefully our new course lays the building blocks to make it easier for schools to take this on and make it a priority.”

Photo Credit: Commons.Wikimedia/NatalieRostran